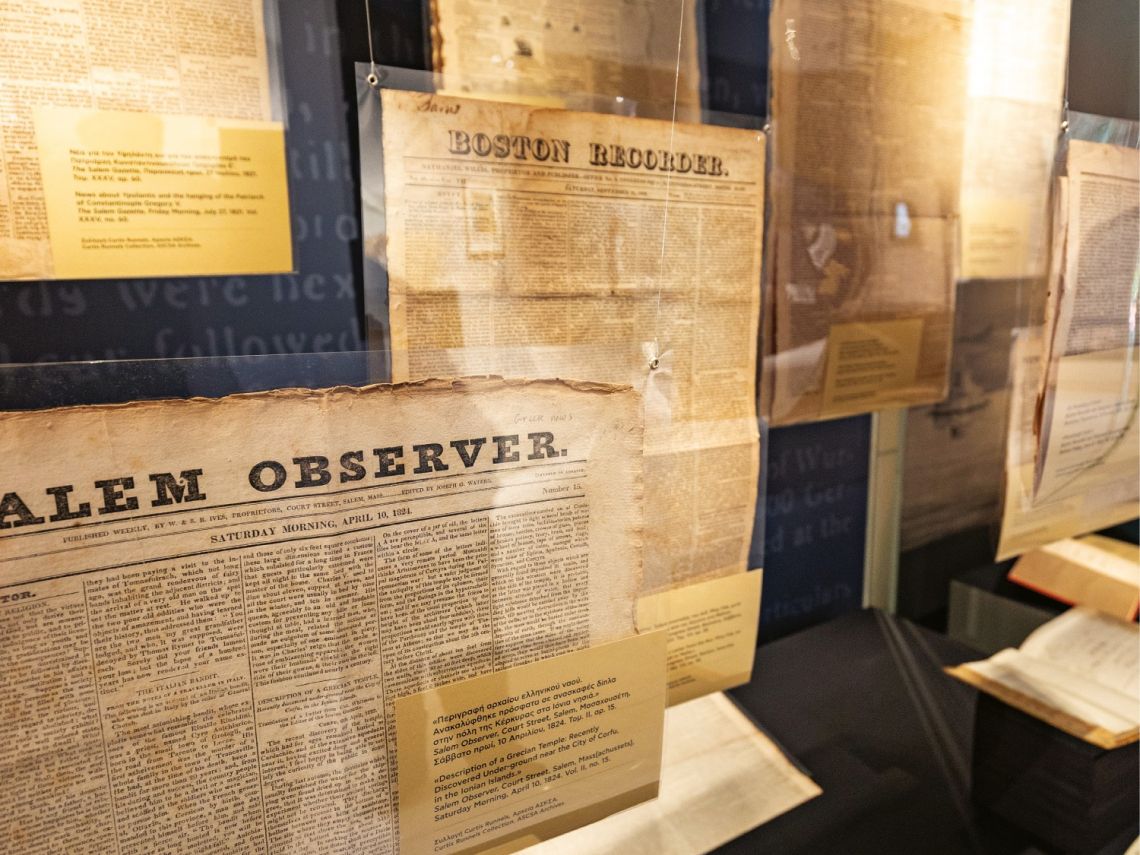

News of the Greek insurrection reached the United States in late May 1821. In addition to reports from correspondents in major European cities, American newspapers also published first-hand accounts of the events of the war written by volunteers who fought in Greece like George Jarvis, whose journals are on display here, Samuel Gridley Howe and Jonathan Peckham Miller.

Because of the Monroe Doctrine of American neutrality in international affairs, America’s humanitarian efforts in support of the Greeks were largely run from the bottom up, by private citizens. Support for the Greek cause spread so fast that it became known as “Greek fever.” Pro-Greek relief committees were organized in America’s major cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, and Cincinnati, to “Save the Greeks!” Through collections, balls, concerts, and calls for help they solicited donations for the relief of the Greeks.

Αt first, these were intended for the purchase of military supplies and were given to the Greek government without any restrictions as to their use. As the Greek civil war started, interest dwindled but thanks to the efforts of the Greek Committees new campaigns were started in 1826 and 1827. Humanitarian help was placed in the hands of American agents sent to Greece who made sure that the aid would be given only for the relief of the women, children, and old men, non-combatants of Greece. This policy met with sharp opposition on the part of the Greek government and the Greek military attempted to seize the supplies more than once.

In 1827-28 six ships from New York or Boston brought to Greece the long-awaited humanitarian aid of a total of $ 140,000. The Tontine, Chancellor, Six Brothers, Levant, Statesman, Jane, Herald and Suffolk sailed in the Mediterranean under the protection of the Mediterranean Squadron, the American navy that had been stationed in the Mediterranean since the Barbary Wars.

Article about the Massacre of Chios. Connecticut Courant, Hartford, Tuesday, August 20, 1822. Vol. LVIII, no. 3004. "The Greek Victory" and information about the destruction of the island of Ipsara. New Hampshire Gazette, Portsmouth, Tuesday, October 22, 1822. Vol. LXVII, no. 48. "Missolonghi Fallen!" Boston Recorder and Telegraph, Congress Street, Boston, Friday, June 23, 1826. Vol. XI, no. 25. “The Turkish and Egyptian Fleet Destroyed.” New Hampshire Patriot & State Gazette, Concord, New- Hampshire, Monday, December 31, 1827. Vol. XIX, no. 978. Thomas L. Winthrop and Edward Everett, Address of the Committee for the Relief of the Greeks, published, Boston 1823. Resolution of the Legislature of South Carolina, expressive of their sympathy for the Greeks in their struggle for independence on January 2, 1824. 18th Congress, 1st Session. [21]. Memorial of the Inhabitants of Boston, on the Subject of the Greeks. January 5, 1824. Read, and ordered to lie on the table. Washington, Gales & Seaton, 1824. Solomon Drown, An oration, delivered in the first Baptist meeting-house in Providence, at the celebration, February 23, A. D. 1824, in commemoration of the birth-day of Washington, and in the cause of the Greeks. Brown & Danforth, 1824. [...] a committee to raise a supply of food and raiment for the suffering and famishing Greeks[...], Philadelphia, Jan. 9, 1827. In January 1827 the Greek Philhellenic Committee of New York engaged Colonel Jonathan Peckham Miller, who had already fought bravely in Greece with Jarvis and knew the Greek language, to supervise the distribution of supplies overseas. Through the efforts of the Committee, Miller was able to collect $17,500 worth of various relief supplies, which he took back to Greece onboard the ship Chancellor, on March 5th, 1827. He also published a book under the direction of the committee. Henry Post, another agent of the New York committee, also published a book. Joseph Partridge, Napoli di Romania. 1827. Watercolor drawing. July 21 [August 2], 1828. Letter of the Governor of Greece Ioannis Kapodistrias to the representatives of the Philhellenic Committee of New York, Samuel Woodruff, Rev. Jonas King και John R. Stuyvesant, expressing the gratitude of the Greek people for the humanitarian aid from the United States. These Americans were responsible for the contents of the ship Herald that arrived in Poros and brought aid valued at $49,800. Service of Diplomatic and Historical Archives, Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Central Service 1827/97/1D, pp.11-12 The “Greek fever” infiltrated popular spectacles, bringing the Greek struggle close to the people. A few months after Mordecai Manuel Noah, his fellow American playwright John Howard Payne who lived in London staged a similar play inspired by Ali Pasha. Article about the Massacre of Chios. Connecticut Courant, Hartford, Tuesday, August 20, 1822. Vol. LVIII, no. 3004. "The Greek Victory" and information about the destruction of the island of Ipsara. New Hampshire Gazette, Portsmouth, Tuesday, October 22, 1822. Vol. LXVII, no. 48. "Missolonghi Fallen!" Boston Recorder and Telegraph, Congress Street, Boston, Friday, June 23, 1826. Vol. XI, no. 25. “The Turkish and Egyptian Fleet Destroyed.” New Hampshire Patriot & State Gazette, Concord, New- Hampshire, Monday, December 31, 1827. Vol. XIX, no. 978. Thomas L. Winthrop and Edward Everett, Address of the Committee for the Relief of the Greeks, published, Boston 1823. Resolution of the Legislature of South Carolina, expressive of their sympathy for the Greeks in their struggle for independence on January 2, 1824. 18th Congress, 1st Session. [21]. Memorial of the Inhabitants of Boston, on the Subject of the Greeks. January 5, 1824. Read, and ordered to lie on the table. Washington, Gales & Seaton, 1824. Solomon Drown, An oration, delivered in the first Baptist meeting-house in Providence, at the celebration, February 23, A. D. 1824, in commemoration of the birth-day of Washington, and in the cause of the Greeks. Brown & Danforth, 1824. [...] a committee to raise a supply of food and raiment for the suffering and famishing Greeks[...], Philadelphia, Jan. 9, 1827. In January 1827 the Greek Philhellenic Committee of New York engaged Colonel Jonathan Peckham Miller, who had already fought bravely in Greece with Jarvis and knew the Greek language, to supervise the distribution of supplies overseas. Through the efforts of the Committee, Miller was able to collect $17,500 worth of various relief supplies, which he took back to Greece onboard the ship Chancellor, on March 5th, 1827. He also published a book under the direction of the committee. Henry Post, another agent of the New York committee, also published a book. Joseph Partridge, Napoli di Romania. 1827. Watercolor drawing. July 21 [August 2], 1828. Letter of the Governor of Greece Ioannis Kapodistrias to the representatives of the Philhellenic Committee of New York, Samuel Woodruff, Rev. Jonas King και John R. Stuyvesant, expressing the gratitude of the Greek people for the humanitarian aid from the United States. These Americans were responsible for the contents of the ship Herald that arrived in Poros and brought aid valued at $49,800. Service of Diplomatic and Historical Archives, Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Central Service 1827/97/1D, pp.11-12 The “Greek fever” infiltrated popular spectacles, bringing the Greek struggle close to the people. A few months after Mordecai Manuel Noah, his fellow American playwright John Howard Payne who lived in London staged a similar play inspired by Ali Pasha.

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

Serial Set Vol. No. 94, Session Vol. No. 2, 18th Congress, 1st Session, H. Doc. 1831.

Collection of Robert McCabe.

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos

Jonathan Peckham Miller, The Condition of Greece in 1827 and 1828. New York: Collins and Hannay, 1828.

Gennadius Library, American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Henry A.V. Post, A visit to Greece and Constantinople in the year 1827-8. New York: Sleight & Robinson, printers, 1830.

Gennadius Library, American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Panoramic view of Nafplio where an American warship, possibly the USS Warren, is anchored. Other ships are anchored behind it.

The Mariners' Museum and Park

In 1822, New York City’s Park Theatre produced a new play by Mordecai Manuel Noah, The Grecian Captive; Or, The Fall of Athens, that was performed on June 17 with great fanfare.

A scale model by the scenographer-architect Edouard Georgiou based on the theatrical aesthetics of the time captures the finale of the play.

After its success in London, the play was also produced in New York. John Howard Payne, Ali Pacha; or, The signet-ring. A melo-drama in two acts. Performed at Covent Garden Theatre, London. New York: E. M. Murden, 1823.

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives. Curtis Runnels Collection

Serial Set Vol. No. 94, Session Vol. No. 2, 18th Congress, 1st Session, H. Doc. 1831.

Collection of Robert McCabe.

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos

Jonathan Peckham Miller, The Condition of Greece in 1827 and 1828. New York: Collins and Hannay, 1828.

Gennadius Library, American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Henry A.V. Post, A visit to Greece and Constantinople in the year 1827-8. New York: Sleight & Robinson, printers, 1830.

Gennadius Library, American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Panoramic view of Nafplio where an American warship, possibly the USS Warren, is anchored. Other ships are anchored behind it.

The Mariners' Museum and Park

In 1822, New York City’s Park Theatre produced a new play by Mordecai Manuel Noah, The Grecian Captive; Or, The Fall of Athens, that was performed on June 17 with great fanfare.

A scale model by the scenographer-architect Edouard Georgiou based on the theatrical aesthetics of the time captures the finale of the play.

After its success in London, the play was also produced in New York. John Howard Payne, Ali Pacha; or, The signet-ring. A melo-drama in two acts. Performed at Covent Garden Theatre, London. New York: E. M. Murden, 1823.

Collection of Konstantinos Arniakos